How do we feel about risk? Generally, when people say that something is “risky,” they’re talking about risk like it’s a bad thing. This tends to be because people spend more time worrying about negative outcomes rather than positive one. But risk is really a neutral idea, not good or bad. Risk is just the chance that something — anything! — could happen. So when it comes to sex and sexual health, how do we start to feel more comfortable with how we understand and perceive risk so that it feels more neutral? What are things we can do to reduce risk of things we don’t want to happen? In this post we’ll talk about pregnancy risks.

Lots of people who have sex don’t always want to get pregnant. Which is fair! Being pregnant, whether it ends in someone giving birth or getting an abortion, is a big deal for a lot of people, and it can really impact their lives. So in general, what is the risk of pregnancy from sex?

When we talk about pregnancy risk, we talk in terms of High Risk and Low Risk. Or we might use like/unlikely, or possible/not possible. Clinicians can’t really calculate if someone is at a 10% or 62% risk for pregnancy. But based on what activities you engage in, or what types of birth control methods you do or don’t use, it’s possible to assume whether what happened had a high risk or low risk of possible pregnancy.

For pregnancy to happen, we need:

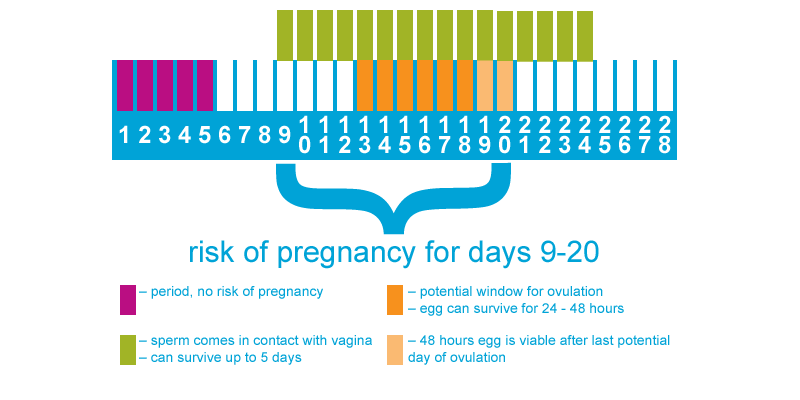

Even if sperm comes in contact with a vagina, nothing will happen without an egg. Ovaries (where eggs come from) release one egg a month. Those eggs are only viable (meaning they can be fertilized by sperm) for 24-48 hours. Here’s a graphic to help illustrate what we’re talking about:

People tend to ovulate 11-16 days before their next period. Assuming a 28-day menstrual cycle, this means that a person is ovulating somewhere between Day 13 and Day 18. If an egg is released on Day 18, it could potentially remain viable until Day 20. So the risk of days where sperm could come into contact with an egg are Days 13-20. Now, since sperm can live for up to 5 days, that means that sperm introduced between Day 9-12 could also still be alive if a person ovulates on Day 13, 14, 15, or 16. So the window where there is a risk of pregnancy from sperm coming in contact with a person’s vagina is only 12 days long, or just under 2 weeks.

People tend to ovulate 11-16 days before their next period. Assuming a 28-day menstrual cycle, this means that a person is ovulating somewhere between Day 13 and Day 18. If an egg is released on Day 18, it could potentially remain viable until Day 20. So the risk of days where sperm could come into contact with an egg are Days 13-20. Now, since sperm can live for up to 5 days, that means that sperm introduced between Day 9-12 could also still be alive if a person ovulates on Day 13, 14, 15, or 16. So the window where there is a risk of pregnancy from sperm coming in contact with a person’s vagina is only 12 days long, or just under 2 weeks.

Since not everyone has a 28-day menstrual cycle, the tricky part is knowing when an egg is going to be released. Some people use period tracking apps or practice a Fertility Awareness Method (FAM) to get a better idea of when they’re ovulating.

| ****NOTE**** |

|

Aside from period trackers or FAM, people often use different methods of birth control to lower their risk of pregnancy. No method of birth control is 100% effective at preventing pregnancy (the highest effectiveness is 99.9%). But that doesn’t actually mean these methods aren’t enough.

Most methods of birth control are given percentages of risk called perfect use and typical use. Let’s use condoms as an example of what this means:

These numbers don’t mean that every condom people use is only 97% effective. If you use a condom and you don’t get pregnant, that mean that condom was 100% effective. These numbers mean that if 100 people used condoms as their main method of birth control for an entire year, maybe 3 of them have to deal with a pregnancy. The 3% risk could come from a rare manufacturing defect in the condom, with most other increases in risk being due to human activity.

Using birth control is a great option for reducing risk of pregnancy. Using multiple methods at the same time is also a great option (condoms + birth control pill, vaginal contraceptive film + pulling out, etc.). Another way to reduce risk is to stick with activities that have no risk of pregnancy (making out, oral sex, masturbating, anal sex). If you’ve had sex where you think there’s a chance sperm could’ve come into contact with a person’s vagina during the risk of pregnancy window, you can try using emergency contraceptive methods like Plan B or Ella (if you use it within 5 days) or a Copper IUD (if you use it within 7 days) to reduce your risk of becoming pregnant. Please note that emergency contraception does not end a pregnancy if it’s already started (i.e., if a sperm has already met and fertilized an egg).

For more on Emergency Contraception Methods, check out our pages on Plan B and Ella [Link], or on the Copper IUD [Link].

More general ways of reducing risk include things like:

Talking to your partner about how you all feel about and understand pregnancy risk, or how you’d like to handle a pregnancy if it happened won’t necessarily reduce risk, but can make it less stressful if a pregnancy does happen. Lots of people only talk about that kind of stuff when a pregnancy does happen, which can be a pretty stressful time to have emotional or serious conversations. Talking about pregnancy ahead of time can help lessen anxiety around the situation.

If you have questions about this topic, feel free to contact one of our peer educators. [Link]

Last Updated: April 2020

*We know that these aren’t the words everyone uses for their bodies (eg. trans folks), and support you using the language that feels best for you.

Check out our OpEd column on Internalized Biphobia written by one of our Peer Sexual Health Educators!

This article talks about Seasonal Affective Disorder, a form of depression that usually affects people in colder, darker months of the year.

Lately we’ve been getting some question about Prostate Play! What is it? Who does it? What even is a prostate? Check out this post for answers to these questions and more!